The Feedback Loop That AI Can’t Replace

In Part 1 of this series, we explored why AI code generation creates an illusion of productivity that collapses when “vibe coding” meets production reality.

Typing code is now trivial. AI handles it faster than humans can type.

But here’s the critical skill: Understanding what that code costs. Where it fails. Why it breaks under load.

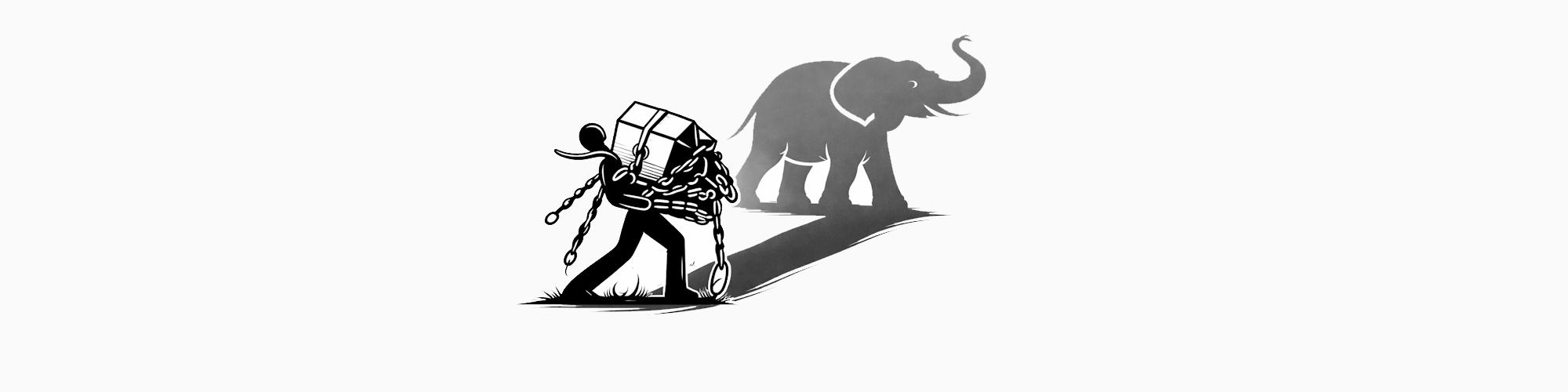

The differentiator between professionals and prompt engineers? The feedback loop.

You write code (or review AI-generated code). Watch it execute. Measure its behavior. Understand its failure modes. Refine your thinking. Each iteration sharpens your ability to recognize what will work before implementing it, what will fail before deploying it, and what will cost more than it’s worth before building it.

So what exactly is this feedback loop? And why can’t AI replicate it?

This article examines the mechanisms that transform abstract thinking into operational understanding:

- Compilers that validate logical consistency and force completeness

- Performance profilers that expose what abstract analysis defers

- Testing frameworks that reveal behavioral gaps

- Production environments that materialize every deferred decision

These aren’t just development tools—they’re thinking validators that expose where reasoning was incomplete. AI can participate in parts of this loop, but it can’t close it. Understanding why reveals why real professionals remain irreplaceable.

The Compiler as Thought Validator

Modern compilers do more than translate syntax—they validate logical consistency. Static analysis, type checking, nullability analysis, and pattern exhaustiveness checks all function as automated reasoning validators. They catch the gaps that pure thought leaves unresolved.

Consider exhaustive pattern matching introduced in C# 8:

public enum OrderStatus { Pending, Confirmed, Shipped, Delivered, Cancelled }

public string GetStatusMessage(OrderStatus status)

{

return status switch

{

OrderStatus.Pending => "Order is pending",

OrderStatus.Confirmed => "Order confirmed",

OrderStatus.Shipped => "Order shipped"

// Compiler error CS8509: The switch expression does not handle all possible values

};

}

The compiler refuses to accept incomplete reasoning. In abstract discussion, you might focus on the “normal” states and unconsciously ignore edge cases. The compiler forces completeness.

Or consider cyclomatic complexity analysis built into Visual Studio and available through analyzers. High complexity scores (typically above 10) indicate control flow that’s difficult to reason about and test thoroughly. The code analyzer doesn’t just flag style violations—it measures cognitive load and highlights where thinking has likely become too tangled to maintain reliably.

// Complexity: 15 (Warning CS1591)

public decimal CalculateDiscount(Order order, Customer customer, DateTime orderDate)

{

if (customer.IsPremium)

{

if (order.Total > 1000)

{

if (orderDate.Month == 12)

return 0.25m;

else if (customer.YearsActive > 5)

return 0.20m;

else

return 0.15m;

}

else if (order.Total > 500)

return 0.10m;

else

return 0.05m;

}

else

{

if (order.Total > 1000 && orderDate.Month == 12)

return 0.15m;

else if (order.Total > 500)

return 0.05m;

}

return 0m;

}

This method might make sense in abstract discussion: “We give discounts based on customer status, order size, and date.” But complexity analysis reveals what abstract thinking hides—the decision tree is convoluted, error-prone, and unmaintainable.

Look closer at the logic: Business rules state that long-term premium customers (6+ years) should get the highest discount (30%) for high-value orders—even better than the December holiday bonus. But a premium customer with 7 years active ordering €1,500 in December only gets 25%—the else if (customer.YearsActive > 5) branch returning 0.20m is unreachable because the December check already returned. The nested if-structure makes the bug invisible in code review but obvious when a test fails:

[Fact]

public void CalculateDiscount_LoyalPremiumCustomer_December_ShouldGetLoyaltyBonus()

{

// Long-term customers should get loyalty discount even in December

var customer = new Customer { IsPremium = true, YearsActive = 7 };

var order = new Order { Total = 1500 };

var date = new DateTime(2025, 12, 15);

var discount = _calculator.CalculateDiscount(order, customer, date);

Assert.Equal(0.30m, discount); // FAILS: Returns 0.25m instead

// The YearsActive>5 branch is unreachable!

}

The code forces you to confront what clean thinking would have structured differently:

// Complexity: 4

public decimal CalculateDiscount(Order order, Customer customer, DateTime orderDate)

{

var rules = new DiscountRuleEngine()

.AddRule(new PremiumCustomerRule())

.AddRule(new HighValueOrderRule())

.AddRule(new HolidayPromotionRule());

return rules.CalculateDiscount(order, customer, orderDate);

}

Refactoring didn’t just clean up syntax—it exposed and resolved structural thinking problems that abstract reasoning missed. The rule engine evaluates all rules and picks the highest discount, making the business logic explicit and the bug impossible.

Performance: Where Theory Meets Production Reality

Algorithmic complexity feels manageable in theoretical discussion. O(n) sounds reasonable. O(n²) seems acceptable for small datasets. O(n log n) feels efficient. Then production traffic hits, datasets grow larger than anticipated, and theoretical complexity translates into CPU cost, memory pressure, and timeout failures.

I’ve debugged production incidents where perfectly logical code—code that passed all functional tests—caused cascading performance failures. Hours wasted. Customer complaints. Emergency hotfixes.

Why? Complexity analysis happened in abstract terms rather than executable measurement.

Example: Nested LINQ queries that looked clean and expressive during development:

// Looks elegant, reads well

public IEnumerable<OrderSummary> GetCustomerOrders(int customerId)

{

return _orders

.Where(o => o.CustomerId == customerId)

.Select(o => new OrderSummary

{

OrderId = o.Id,

Total = o.LineItems.Sum(li => li.Price * li.Quantity),

ItemCount = o.LineItems.Count,

Categories = o.LineItems

.Select(li => li.Product.Category)

.Distinct()

.OrderBy(c => c.Name)

.ToList()

})

.OrderByDescending(s => s.Total)

.ToList();

}

This code communicates intent clearly. In abstract reasoning, it feels straightforward: “Get orders, calculate summaries, sort by total.” But execute it with real data and watch database query patterns, memory allocations, and execution time:

- Multiple database round trips per order (N+1 query problem)

- Repeated calculations over the same collections

- Unnecessary allocations for intermediate collections

- Linear scans for categories on every line item

The abstract reasoning missed what executable profiling makes obvious:

// Same intent, different execution characteristics

public async Task<IEnumerable<OrderSummary>> GetCustomerOrders(int customerId)

{

var orders = await _context.Orders

.Where(o => o.CustomerId == customerId)

.Include(o => o.LineItems)

.ThenInclude(li => li.Product)

.ThenInclude(p => p.Category)

.AsNoTracking()

.ToListAsync();

return orders

.Select(o => new OrderSummary

{

OrderId = o.Id,

Total = o.LineItems.Sum(li => li.Price * li.Quantity),

ItemCount = o.LineItems.Count,

Categories = o.LineItems

.Select(li => li.Product.Category.Name)

.Distinct()

.Order()

.ToList()

})

.OrderByDescending(s => s.Total)

.ToList();

}

Code forced the performance implications into measurable form. Profiling revealed what abstract thought deferred—database round trips, allocation patterns, execution cost. Without writing and measuring executable code, these consequences remain invisible.

The Feedback Loop Programming Provides

Programming isn’t just thinking’s output—it’s thinking’s verification mechanism. The discipline of translating thought into executable form exposes inconsistencies, reveals missing decisions, and surfaces consequences that abstract reasoning defers.

This feedback loop operates at multiple levels:

Compilation: Immediate Logical Feedback

The compiler catches type mismatches, null reference possibilities, exhaustiveness gaps, and logical inconsistencies within seconds. No mental review provides this consistency and speed.

Testing: Behavioral Verification

Unit tests, integration tests, and property-based tests validate that your mental model of system behavior matches actual execution. I’ve written tests expecting specific behavior only to discover the code does something entirely different—not because implementation was wrong, but because reasoning was incomplete.

[Fact]

public void CalculateDiscount_PremiumCustomer_HighValue_December_Returns25Percent()

{

// Test reveals the logic we thought we implemented doesn't match what we actually coded

var customer = new Customer { IsPremium = true, YearsActive = 3 };

var order = new Order { Total = 1500 };

var date = new DateTime(2025, 12, 15);

var discount = _calculator.CalculateDiscount(order, customer, date);

Assert.Equal(0.25m, discount); // Fails: Returns 0.15m instead

}

The test didn’t catch a bug in isolation—it caught incomplete thinking that manifested as unexpected behavior. Without executable code and explicit testing, that gap stays hidden until production.

The AI Testing Trap

AI can generate tests as easily as it generates implementations. Ask for unit tests, and you’ll get methods that exercise code paths and verify outputs. This creates a dangerous illusion: high code coverage with low confidence.

AI-generated tests typically verify happy paths—the scenarios explicitly described in prompts. They rarely test:

- Edge cases that emerge from domain understanding

- Concurrency issues that only appear under load

- Error propagation through system boundaries

- Integration failures when dependencies behave unexpectedly

- Performance degradation with realistic data volumes

I’ve reviewed codebases with 90%+ test coverage where AI generated both implementation and tests. Every test passed. Yet production revealed critical bugs because the tests verified that the code did what it was written to do, not that it solved the actual problem correctly.

The professional’s advantage: knowing what to test comes from understanding how systems fail in production. That knowledge can’t be prompted—it must be experienced, internalized, and applied deliberately.

Profiling: Performance Reality Check

Profilers measure actual CPU consumption, memory allocation patterns, I/O bottlenecks, and threading contention. Abstract complexity analysis (Big-O notation) provides theoretical bounds. Profiling provides operational reality.

Visual Studio’s .NET Object Allocation tool shows exactly which code paths allocate memory and how much. BenchmarkDotNet provides precise execution timing with statistical analysis. These tools don’t just measure code—they validate or invalidate reasoning about performance characteristics.

[MemoryDiagnoser]

public class StringBuildingBenchmark

{

[Benchmark]

public string ConcatenationInLoop()

{

string result = "";

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++)

result += i.ToString(); // Abstract: "Should be fine for 1000 iterations"

return result;

}

[Benchmark]

public string StringBuilderInLoop()

{

var builder = new StringBuilder();

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++)

builder.Append(i);

return builder.ToString();

}

}

// Results expose reality abstract thinking missed:

// ConcatenationInLoop: 3,450 μs, allocated: 2,031,616 B

// StringBuilderInLoop: 45 μs, allocated: 24,624 B

The difference between “seems reasonable” and “actually performs” is 75x execution time and 80x memory allocation. Abstract reasoning deferred these consequences. Executable code and measurement made them visible.

Production: Ultimate Reality Validation

Production exposes every assumption abstract thinking made: scale, concurrency, failure modes, dependency availability, network latency, operational complexity. Code that worked flawlessly in development reveals hidden assumptions when deployed at scale with real users, real data, and real failure conditions.

Monitoring, telemetry, and distributed tracing provide feedback about system behavior under actual conditions. Without executable code running in production, all architectural reasoning remains theoretical.

Programming and Thinking: Inseparable, Not Sequential

The original framing positioned thinking and programming sequentially: think first (the hard part), then program (the easy translation). This model fundamentally misrepresents the relationship.

Programming and thinking are inseparable, iterative, and mutually reinforcing:

- Abstract thinking identifies problems, explores solution spaces, and proposes approaches.

- Code writing forces abstraction into precise, executable form, exposing gaps and inconsistencies.

- Execution and measurement reveal consequences—performance, resource consumption, failure modes—that abstract thought deferred.

- Refinement incorporates execution reality back into thinking, improving the mental model.

- Repeat until thinking and execution align.

Neither operates effectively alone. Thinking without code stays vague and unvalidated. Code without thinking becomes mechanical translation without understanding. High-quality software emerges from tight iteration between abstract reasoning and executable verification.

This isn’t pedantry about implementation details. This is recognition that software engineering is fundamentally about managing complexity in executable systems. Complexity that can’t be reasoned about produces brittle, unmaintainable systems. Complexity that remains purely abstract never confronts operational reality.

The discipline of programming (writing code, measuring behavior, refactoring based on feedback) is how abstract thinking becomes operational reality. It’s not the easy part that follows hard thinking. It’s the verification mechanism that sharpens thinking and exposes where reasoning was incomplete.

What Makes Professionals Irreplaceable

Compilers validate logic. Tests reveal behavioral gaps. Profilers measure performance reality. Production exposes every deferred decision. These tools generate feedback constantly.

But feedback is worthless without interpretation. And interpretation requires experience.

When a profiler shows 75x performance degradation, the junior developer sees a red flag. The senior engineer sees a memory allocation pattern they’ve debugged before, recognizes the architectural constraint it reveals, and knows three ways to fix it based on context. When production monitoring shows intermittent timeout spikes, AI suggests retry logic. The experienced architect recognizes a connection pool exhaustion pattern and addresses the root cause.

The irreplaceable skill isn’t generating code. It’s closing the feedback loop.

That means watching code fail, understanding why it fails, and refining your mental model until your intuition predicts failure modes before they manifest. AI participates in generating code and even in analyzing errors. But it can’t internalize the lessons. It can’t build the judgment that comes from years of production incidents, debugging sessions, and architectural decisions that played out over time.

In the final part of this series, we’ll examine what this means for professional development. When code generation is commoditized, what skills actually matter? How do you build the cognitive architecture that AI can’t replicate?

The answer shapes how we train developers, evaluate expertise, and define what “senior engineer” means in an AI-augmented world.

Comments